|

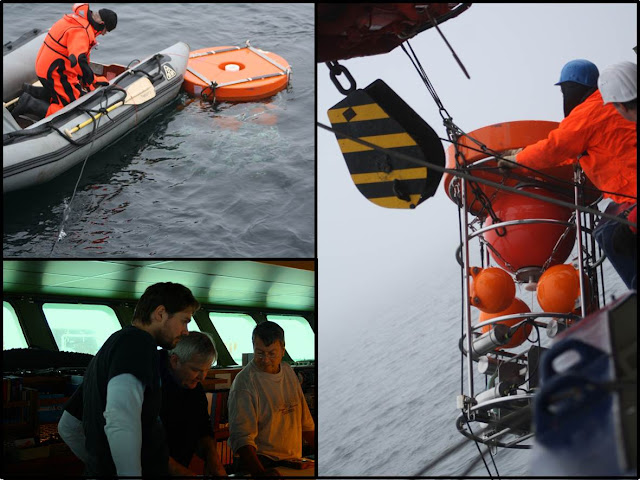

Hielo sobre el Gakkel Ridge en el Ártico. Ice-float

above the Gakkel Ridge in the Arctic Ocean. Source: Raquel Somavilla

|

Como podéis

suponer el nombre de mi blog ‘From The Blue Side’ está relacionado con el hecho

que vivimos en un planeta azul, y ello es debido a que los océanos cubren más

del 70% de la superficie de nuestro planeta. El porqué del giňo al lado oscuro

os lo contaré otro día. La parte ‘divertida’ de que nos referiramos a nuestro

planeta como el Planeta Azul, es que esto es así desde que las primeras

imágenes de la Tierra vista desde el espacio nos han convencido de ello. ¿Qué hay de divertido en esto? Pues que hemos

necesitado ir al espacio para reconocer la importancia de los océanos en

nuestra vida, y sin embargo en el aňo 2000 todavía la mayoria de las áreas del

oceáno de nuestro planeta no habían sido muestreadas desde la superficie hasta

el fondo más de una vez (Stewart, 2008).

As you can imagine, the name of my blog ‘From the Blue

Side’ is related to the fact that we live on a blue planet due to the ocean

covers over seventy percent of its surface (I will explain you the reference to

‘the dark side’ in the title of the blog in other moment). The funny part that

we call our planet the Blue Planet is that we do since the first images of the

Earth from the space have convinced us of this fact. Which is the funny part?

Well, we have needed to go to the space to realize about the importance of the

ocean in our lives, while, by the year 2000, most areas of the ocean had been

sampled from top to bottom only once (Stewart, 2008).

La situación ha

mejorado pero el fondo de nuestros océanos sigue siendo un gran desconocido.

Hay procesos que en parte intuimos como ocurren pero que todavia no han sido

observados. Otros han sido observados pero no lo suficiente como para entender

sus implicaciones en el océano. Es el caso de la actividad hidrotermal. ¿Por

qué a un oceanográfo puede interesarle la actividad geothermal? Os lo cuento enseguida, pero me llevará un poco. Leed

hasta el final, no seáis vagos! ;-)

The situation has significantly improved, but still

the deep ocean is a big unknown. There are processes that we guess how they

work, but they have not been observed yet. Others have been observed, but not

enough for a complete understanding of their implications in the ocean. This is

the case of the hydrothermal activity. Why is an oceanographer interested in

hydrothermal activity? I tell you in one moment, but it will take me a while.

Read until the end, don`t be lazy! ;-)

La actividad hidrotermal en el fondo del océano se asocia a la presencia de margenes divergentes entre placas, lo que se conoce también como dorsales medioceánicas como la que encontramos en medio del Atlántico (Fig. 2) y por la que la salida de material magmático hace que los bordes de los continentes europeo y americano se separen. La presencia de fracturas en el subsuelo marino en estos lugares permite que el agua del fondo entre en contacto con material magmático del interior de la Tierra. Eso hace que las aguas que penetran a través de dichas fracturas adquieran temperaturas muy altas (300-400°C) de manera que cuando emergen de nuevo hacia el fondo del oceano ascienden rápidamente en la columna de agua al ser menos densas que el agua que las rodea. Imaginaros la chimenea de una fábrica por la que sale vapor de agua. El vapor de agua asciende rápidamente como nube blanca que se va diluyendo en la atmósfera hasta que su densidad es igual a la del aire que la rodea. Volviendo a nuestra ‘nube’ hidrotermal, durante su ascenso en la columna de agua va incorporando agua profunda del océano más fría y con mayor salinidad de manera que se va enfriando y haciendo más densa. Cuando su densidad es igual a la del agua que la rodea su ascenso finaliza, a veces varios cientos de metros por encima del fondo marino. Así pues, la actividad hidrotermal supone una inyección de calor a las capas profundas del océano, asi como un transporte de masas de agua debido a los movimientos verticales que os acabo de describir. Las aguas profundas de los océanos se renuevan muy lentamente y en algunos lugares los transportes inducidos por la actividad hidrotermal podrían ser comparables a los necesarios para la renovación de dichas aguas profundas (Lupton et al., 1985)

The hydrothermal activity is associated with the presence of divergent plate boundaries, also known as mid-ocean ridges as that in the mid-Atlantic where the discharge of magmatic material makes the European and American continental margins separate. The presence of fractures in the ocean bottom in these regions enables the contact between the bottom sea-water with the magmatic material below. It makes that the bottom sea-water penetrating along these fractures get very high temperatures (300-400°C) in such a way that when they merge towards the deep ocean again they ascend through the ocean water column due to they are lighter than the surrounding waters. Imagine the chimney of a fabric through which water vapor is released. The water vapor ascends quickly as a white plume that dilutes in the atmosphere until its density is equal to the air at the same level. Returning to our hydrothermal plume, during its ascent, it entrains ambient deep ocean water, colder and saltier, that makes increase its density. This upward movement continues until its density is equal to the ambient water, sometimes several hundred meters above the seabed. Thus, the hydrothermal activity implies a heat injection to the deep ocean, as well as a transport of water masses due to the vertical movements that I have described. The deep water masses in the different ocean basins are very slowly renovated, and, in some places, the transports produced by hydrothermal plumes can be comparable with the magnitude of flows predicted for these basins (Lupton et al., 1985).

|

| Fig. 2. Situacion de la dorsal Atlántica y Gakkel Ridge en al Ártico. Location of the mid-Atlantic Ridge and the Gakkel Ridge in the Arctic. Source: Raquel Somavilla |

Pero no es sólo calor lo

que se intercambia entre el fondo y el océano a través del agua que penetra y

posteriormente emerge a través de esas fracturas, sino diferentes metales y

compuestos que se encuentran en distinta concentración en el océano y en el

interior de la Tierra. Por ese motivo, la actividad hidrotermal afecta la

química del océano (Stein et al., 1995), proporcionando incluso una fuente de

energía alternativa que es capaz de mantener ecosistemas únicos que distan a

veces entre una zona de actividad hidrotermal y otra. Nuestras ‘nubes’ de agua hidrotermal no

contienen oxígeno pero son ricas en ácido sulfídrico (H2 S), el cual

puede ser usado por bacterias como fuente de energía para la producción de

material orgánica que después mantiene cada uno de esos ecosistemas a pequena escala

(Longhurst, 1998).

Nevertheless, it is not only heat what is exchanged between the ocean

bottom and the water column through the water penetrating and later emerging

through those fractures but different metals and compounds that exist in

different concentration in the ocean and the Earth interior. For this reason,

the hydrothermal activity affects the chemistry of the ocean (Stein et al.,

1995), even providing an alternative energy source able to maintain unique

ecosystems differing sometimes from one hydrothermal vent to another. Our

hydrothermal ‘clouds’ do not contain oxygen, but they are rich in hydrogen

sulfide (H2 S), which can be used by some bacteria as energy source

to produce organic matter that later maintains each of these small-scale ecosystems

(Longhurst,

1998).

En el Ártico encontramos

uno de esos márgenes divergentes entre placas a los que se asocia la actividad

hidrotermal. El Gakkel Ridge es una extensión de la dorsal medio oceánica más al

sur en el Atlantico. Tiene una longitud de unos 1800 km. y cruza el Ártico

desde las costa de Groenlandia hasta Siberia (Fig. 2). Como el resto del

Ártico, es una de las zonas océanicas menos exploradas por lo que cuál es la

importancia de la actividad hidrotermal en todos los procesos que os he

comentado más arriba es todavia una pregunta sin contestar. La actividad

hidrotermal podría tener implicaciones de mayor importancia aquí debido a que

las capas profundas (últimos 2000 metros) están menos estratificadas que en

otros océanos. Eso significa que en el Ártico la diferencia de densidad entre

agua a diferentes profundidades es menor. Por tanto, nuestras ‘nubes’ de agua

hidrotermal podrían ascender más en el Ártico. Ello movería un mayor volumen de

agua verticalmente, siendo mayor también su contribución a la circulación de

masas de agua profundas en esta cuenca. Por supuesto, el calor liberado al

océano a través de la actividad hidrotermal también afectará al calor

almacenado en el fondo del Ártico. Así que, estoy encantada de que durante

nuestra campana hayamos podido obtener medidas sobre el Gakkel Ridge, y que

esos nuevos datos puedan ayudarme a intentar encontrar respuesta a alguna de

esas preguntas. Para los que no lo sepan las aguas profundas del Ártico y Mar

de Groenlandia son mi objetivo de estudio actualmente.

In the Arctic, we find one of these divergent plate boundaries associated

with hydrothermal activity. The Gakkel Ridge is an extension of the

world-encircling ridge, represented further south in the Atlantic by the

mid-Atlantic Ocean Ridge, through the Arctic Ocean. It extends along 1800 km.

crossing the Arctic from Greenland to Siberia (Fig. 2). As the rest of the Arctic

Ocean, it is one of the less sampled oceanic areas, and so the importance of

the Gakkel Ridge hydrothermal activity in all the processes that I explained

above is still an open question. The hydrothermal activity in the Arctic could

have larger implications than in other basins, because its deeper layers are

less stratified than other ocean basins. It means that here the density

difference between different depths is smaller. Thus, the hydrothermal ‘plumes’

may reach shallower depths in the Arctic. It would imply a larger vertical

movement of water, being also higher its contribution to the circulation of the

deep water masses in this basin. Of course, the heat released to the ocean by

hydrothermal activity will also affect the heat storage in the deep Arctic

Ocean. Thus, I’m really happy and excited with the idea that we have sampled

above the Gakkel Ridge, and that these data will help me to give insight in

these questions. For those that don’t know, the deep water masses of the Arctic

and the Greenland Sea are the aim of my research nowadays.

No puedo terminar sin

contaros otra cosa más y con esto os prometo que acabo. El Océano Ártico está

comunicado con el resto de oceanos desde hace relativamente poco en su historia

geológica, no existiendo todavía hoy ningún paso suficientemente profundo como

para intercambiar agua a la profundidad en que esta actividad hidrotermal

tienen lugar. Por tanto, es esperable que nuevas especies que hayan

evolucionado aisladas y se hayan adaptado especialmente a las condiones del

Ártico y la actividad hidrotermal estén todavía por descubrir (Edmonds et al., 2003).

I can’t finish without telling you one more thing, but with this I

finish. I promise. The Arctic Ocean is connected with other ocean basins for

relatively little time in its geological history. Besides, there is no opening

nowadays deep enough that enables the direct exchange of water at the depth

where the hydrothermal activity in the Gakkel Ridge takes place. Thus, we can

expect that new species which have evolved in isolation and adapted to the

Arctic and hydrothermal vent environments will be discovered here (Edmonds et

al., 2003).

References:

Edmonds et al., 2003.Discovery of

abundant hydrothermal venting on the ultraslow-spreading Gakkel ridge in the

Arctic Ocean. Nature, Vol. 421. 2003

Longhurst,

A. (1998), Ecological Geography of the Sea, Academic Press London.

Lupton

et al., 1985. Entrainment and vertical

transports of deep-ocea water by hydrothermal plumes. Nature, Vol. 316. 1985.

Stein et al., 1993.‘Heat flow and hydrothermal circulation‘ in

‘Seafloor Hydrothermal Sytems: Physical, Chemical, Biological and Geological

Interactions‘. Geophysical Monograph, 91. American Geophysical Union.

Stewart, R. H. (2008), Introduction

To Physical Oceanography, 2008 ed., free downlable, Department of

Oceanography Texas A & M Univer