We have almost done half of our cruise in the Arctic. Today, we start

our return trip from the Laptev Sea (in front of the Siberian Coast) to

Bremerhaven (where I live now and where AWI is located) passing through the

North Pole. The last 10 days have been very busy, and, for this reason, I

haven’t had plenty of time to write any post for the blog and tell you what was

happening during that time. Besides, the last ice-station was not very lucky

for us, things didn’t go as we expected, and I thought I didn’t have a lot of

things to tell you. I was wrong, and that has given me a theme for this post.

|

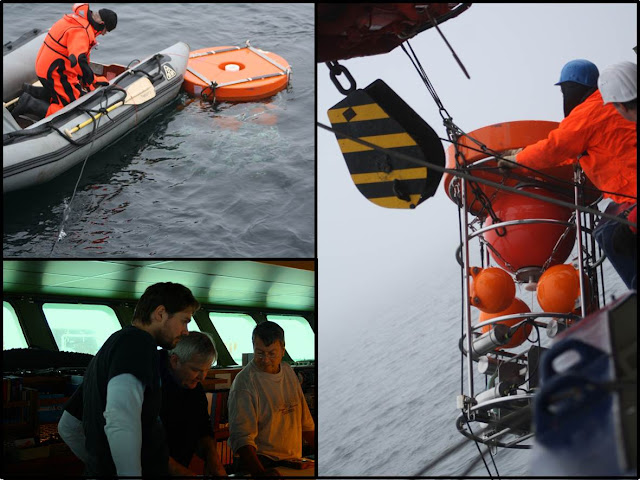

| Material necesario y algunas fases de la colocación de un ITP. Material and some steps during an ITP deployment. Source: Raquel Somavilla |

Así pues, hoy no

solo os voy a hablar de éxitos, de resultados asombrosos y de instrumentos

extraordinarios que nos permiten observar cosas que hasta hace poco parecían

imposibles sino también de todo el esfuerzo que hay detrás de todos esos

resultados, y el que a veces nos olvidamos de mencionar.

Thus, today I will not tell you only about big successes, amazing results

and/or extraordinary instruments that allow us the observation of processes

that until recently we couldn’t imagine. Today, I will tell you also about the effort

that is behind all these advances, and that sometimes we forget to

mention.

Las fotos que tenéis

más arriba se corresponden con el material y la colocación de un ITP (Ice-tethered Profiler) en el

hielo. Un ITP es CTD (para los que no sepáis lo que es

un CTD podéis mirar el post anterior ‘New Eyes to see the Ocean’) perfilador autónomo, lo que significa

que es un instrumento que toma perfiles

de la columna de agua de manera automática,

midiendo temperatura, salinidad y presión como el resto de CTDs, aunque

pueden añadirse otros sensores. Para ello, el perfilador va montado sobre un

cable de 800 metros de longitud dotado en el fondo de un muerto que lo mantiene

vertical y unido en la superficie del hielo a una boya (la boya amarilla que

véis en la foto). De este modo, el perfilador realiza unos dos o tres perfiles

al día desde unos 800 metros de profundidad hasta la superficie debajo del

hielo. Desde la boya en superficie los datos son enviados vía satélite según

son tomados. Esto permite conocer como el hielo va derivando en el Ártico -el

hielo no se mantiene estático sino que se forma y posteriormente deriva

empujado por el viento fuera de éste a través principalmente de Fram Strait- así

como las propiedades de las masas de agua debajo de este. La mayoría de las

medidas en zonas polares se toman durante los meses de verano cuando la

extensión y espesor del hielo permiten realizar campañas oceanográficas. Estos

instrumentos permiten obtener medidas durante todo el año que de otra manera no

pueden realizarse. Por eso, suponen un gran avance y durante nuestra campana

tenemos la intención de colocar 5 instrumentos de este tipo en distintas áreas

del Ártico. Nos quedan tres.

The photographs that you see above correspond with the material and

deployment of an ITP (Ice-tethered

Profiler) on the ice. An ITP is an autonomous CTD (for those that don´t

know what a CTD is, you can read the previous post ‘New Eyes to see the Ocean’)

profiler. It means that this

instrument makes profiles of the

water column automatically, measuring

temperature, salinity and depth as the rest of CTDs, although other sensors

can also be installed. The profiler is

mounted over a cable of 800 m. length equipped with a weight at the bottom that

maintains the cable vertically orientated and joined to a superficial buoy on

the ice surface (the yellow buoy that you see in the photograph). Once it has

been installed, the ITP makes two or three profiles per day from 800 meters

depth to the surface below the ice. From the surface buoy, the registered data

are sent by satellite. It allows knowing how the ice drifts in the Arctic Ocean

-the ice is not static, but it forms inside the Arctic Ocean and lately it is transported

by the winds out from the Arctic Ocean- and the properties of the water column

below the ice. Most of the oceanographic measurements in Polar Regions are

taken during summer months when sea ice extension and thickness allow the

sampling. These instruments enable to obtain measurements during the whole year

that are not possible to be carried out in other way. For this reason, they represent

a big advance, and we have the intention to deploy five of this type of

instruments during our cruise. We still have to

deploy three of them.

Como os decía, lo

que quiero destacar esta vez no es solo lo que estos instrumentos nos

proporcionan sino todo lo que conlleva poner estos aparatos en funcionamiento.

As I told you, today I not only want to highlight the ‘goodness’ of these

new instruments, but also all the effort involved in putting them into

operation.

1- Para empezar debemos mover todo el material al hielo, lo

cual no es una nimiedad teniendo en cuenta que todo junto pesa alrededor de una

tonelada. Arriba a la izda. en la foto veis la mayoría del material necesario

para colocar uno en sus distintas cajas.

First, we must move all the material onto the ice,

which is not a triviality considering that all together weighs within 1 ton.

Above, on the top-left corner photograph, you can see most of the material that

we need for an ITP deployment.

2- Después hay que montar todo el material auxiliar para

poder desplegar el cable de 800 metros, colocar el perfilador y la boya en

superficie. Previamente habremos hecho un agujero en el hielo de unos 3 metros

de profundidad. Pueden ser 2 ó 4.5 metros dependiendo del espesor del hielo. Como

veis en la foto de abajo a la izda. tampoco es un juego de niños. Todo lo que veis

ahí, estaba inicialmente dentro de las cajas.

Later, we must assemble all the auxiliary material

that enables to lay out the 800 m. of cable together with the weight in the

bottom, the deployment of the profiler, and the surface buoy. Previously, we will have done a hole in the

ice of three meters depth on average. It can be 2 or 4.5 depending on the ice

thickness. As you see in the photograph in the bottom-left corner, it’s neither

a child’s game. All that you see there were initially inside the boxes.

3- Una vez colocado todo, se comprueba que el perfilador

funciona, se vuelve a meter todo el material auxiliary en las cajas, de manera

que cuando nos vamos solo la boya de superficie que veis en la foto de arriba a

la dcha. indica que hemos estado ahí y colocado un ITP.

Once the ITP has been deployed, a test is carried out

to check its performance. Then, all the auxiliary material is put again inside

the boxes, in such a way that when we leave only the presence of the surface

buoy indicates that we have been there, and that an ITP is deployed there

(photograph in the top-right corner).

4- ¿Y qué pasa si el perfilador no funciona? Pues hay que

volver a recoger los 800 metros de cable en el tambor, recuperar el perfilador

con su muerto de 150 kilos, guardar la tonelada de material de nuevo en sus

cajas y volver con todo al barco. A veces pasa, pero este esfuerzo es necesario

para obtener todos estos nuevos datos que después están a disposición de toda

la comunidad científica y del público en general, lo cual hace ese trabajo aún

más merecedor de ese esfuerzo.

And…what happens if the profiler doesn’t work? Well,

then, we must to put the 800 meters of cable again in the winch; to recover the

profiler and the weight at the bottom; and to keep the ton of material again in

their boxes, and return it to the ship. Sometimes, this kind of things happens,

but this effort is necessary to obtain these new data that later will be

available for all the scientific community and the general public. It makes this

work even more worthy of this effort.

Y todo esto me da pie a hablar de otro trabajo que también

pasa desapercibido para el público; bueno, eso considerando que nuestro trabajo

como oceanógrafos es sobradamente conocido ;-). Ese es el trabajo de los

miembros de la tripulación de los barcos oceanográficos. Para prácticamente

todo lo que realizamos a bordo durante una campana necesitamos su ayuda. Sin

ellos, cualquier cosa que quisiésemos realizar sería mil veces más complicada,

suponiendo que consiguiésemos llegar a hacerla. Es increíble a la velocidad que

pueden hacer y deshacer nudos, manejar tornos, desplegar zodiacs en el agua y

recogerlas, o hacer con el barco y su navegación lo que nosotros queramos o

necesitemos. Incluso disponemos de un helicóptero con el que con la ayuda de

los pilotos y el resto de personal podemos hacer incluso más cosas, o intentarlas

de manera diferente, por si todo lo hecho en el barco no fuese suficiente. Hoy

en lugar de fotos del hielo, os dejo algunas fotos de ellos.

Source: Raquel Somavilla

Overall, it has made me think in other work that also goes unnoticed for

the public; of course, this considering that our work as oceanographers is well

known ;-). This is the work of the members of the crew of a research vessel.

For almost everything that we do onboard, we need their help. Without them any

task would be thousand times more difficult, assuming that we would be able to do

in such case. It’s incredible how fast they can do and undo knots, to operate

the winch, to put zodiacs in and out of the water, and make with the ship and

its navigation anything that we need. Even, we dispose of two helicopters with

which we can try alternative maneuvers to all the previous done onboard with

the help of the pilots. Today, instead of ice photos, I leave you photos of

some of them.

Source: Raquel Somavilla

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario

Muchas gracias por tu comentario.

Many thanks for your comment.

Raquel